How and why capital fled Catalonia

The global repercussion of the Catalan crisis has alarmed international companies, pushing them to move their legal headquarters

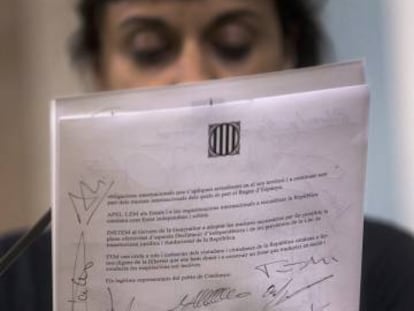

The decision made by Catalan companies and banks to move their corporate headquarters out of the region has dealt what could be a definitive blow to the regional government’s secessionist plans. But the decisions have had more to do with pressure from the world’s financial capitals than to voices from within Catalonia and Madrid.

Following the October 1 independence referendum, Catalan companies received a deluge of calls from international credit rating agencies and investment fund managers, all delivering the same message: Catalonia has become synonymous with uncertainty, and uncertainty is something the markets hate.

For long enough, the Catalan problem has been swept under the carpet by foreign investors, but when images of police violence started circulating and the region’s independence bid suggested a euro exit, alarm bells started to ring.

Most companies never imagined that international investors would become so twitchy A businessman from the region

One businessman working in communications says that “most companies never imagined that international investors would become so twitchy. They never thought it would come to this. Never.”

Another destabilizing factor is the prospect of a Catalan treasury. If such an entity is established, it could mean companies being hit twice on corporate tax – once by Spain and again by Catalonia. Hence, Catalonia has seen asset managers withdrawing and companies relocating.

But what if these companies hadn’t waited for global forces to pressure them into relocating and had instead taken the initiative themselves? On October 8, Josep Borrell, former minister and vice president of the European Parliament, criticized the deafening silence from Catalonia’s business sector. “Couldn’t you have spoken up before?” he said. “Why didn’t you say publicly what you were saying in private? If you had, we could have avoided this.”

Antón Costas, economics professor and former president of the Economy Circle – the most influential business lobby in Catalonia – had this answer: “I believe that we did see this coming. José Manuel Lara, former president of [publishing group] Planeta did; Josep Oliu, from Sabadell did; and José Luis Bonet, from Freixenet did as well as the Chamber of Commerce. But I don’t believe that businessmen should continually be expected to venture their opinions on politics, and even less so in a debate that has been running for five years. Nor can companies be expected to be delivering this kind of message, given the effect it would have on investors and on the company itself.”

“We told Puigdemont, but he didn’t want to believe us”

It seems that what wasn’t said in public was said in private. “I once told Artur Mas that to come out of the EU would be very risky,” says Professor Pedro Nueno. “And he replied, ‘We won’t leave the EU for one minute, ever.’ So I asked him why he didn’t make that clear. He must have said the same to other businessmen.”

Other influential figures from academia and the banking and business sectors insist that they warned members of the regional government of the serious economic risks of breaking away from Spain. “It’s true that we may not have said enough in public,” says one member of the Catalan association Work Support. “But we did speak to Mas and Puigdemont in private. We told them this could happen, but they didn’t want to believe it. They wanted to believe those who were saying this would never happen.”

The 2015 elections won by the pro-independence parties prompted the first exodus, including hoteliers Jordi Clos and Pau Guardans, who claimed to be moving for tax purposes. In August, health-food retail chain Naturhouse left citing “management issues” as the company has had offices in Madrid since it went public in April 2015. But its president, Félix Revuelta, has long been critical of the Catalan government’s plans for secession. “It is terrifying the business sector,” he said in May.

Eduardo Serra, a government minister during the Aznar era, says: “I have been speaking recently to Catalan bankers and businessmen and they all say, ‘I know independence would be ruinous for my company, but if I say as much to the regional government, they’ll destroy me’.”

A source close to Sabadell President Josep Oliu recalls that before the informal self-determination referendum on November 9, 2014, Oliu privately warned the then-president Artur Mas that if he continued to push for independence, he would force Sabadell out of Catalonia. According to the source, Mas was incredulous and maintained that they would never be forced to leave the EU.

In public, the president of Spain’s fifth-largest bank was the first to speak out, describing the situation as “worrying,” and telling an audience in Oviedo on October 3 that he was prepared to leave Catalonia to protect his customers, shareholders and staff. In an unsteady voice, he declared that Sabadell would always take operative decisions based on economic and regulatory criteria to boost business in the main market – the Spanish market. He added: “I can assure you that, if necessary, the bank will take the necessary measures to protect the interests of our customers within the framework of the European Union and ECB Banking Supervision.”

Meanwhile, CaixaBank adopted a more cautious position. “No decision has been taken,” said a spokesman. “When independence is declared, if it becomes a reality, we will act to defend our customers, staff and shareholders.”

What Sabadell and CaixaBank were always clear about was that both banks should leave at the same time, which is what they have done

On October 5, Sabadell announced it would be moving its legal headquarters to Alicante and the following day CaixaBank announced its move to Valencia.

But why did the banks and companies not react publicly before? It is true that on January 13 this year Oliu suggested that Sabadell would leave Catalonia if an independent Catalonia was left outside the EU. However, several weeks later, he claimed his words had been misinterpreted and suggested that the headquarters would remain in Catalonia. Meanwhile, Jaume Guardiola, managing director of Sabadell, spoke out on September 13 in Bilbao, declaring that if there was a yes vote in the referendum, there would be “changes of address.”

Executives now admit that information being passed to them by the regional government on a soft and negotiated exit encouraged reticence on their behalf. It was said that, in the worst case scenario, they could have two headquarters, one in Madrid and one in Barcelona, one for each market. An internal boycott was something to be avoided: CaixaBank has €68 billion in deposits in Catalonia and Sabadell has €24 billion – sums that would seriously affect the economy if they pulled out.

However, it has been the number of cash withdrawals in the rest of Spain in recent days that has forced the banks to adopt strategies to reassure their customers. What Sabadell and CaixaBank were always clear about was that both banks should leave at the same time, which is what they have done.

In their defense, the banks flag up a joint statement made on September 18, 2015, to the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the Spanish Savings Banks (CECA), warning that they would leave an independent Catalonia. “The result was disastrous,” says a spokesman. “We were boycotted by certain Catalan organizations and customers who withdrew their money just as they are doing now. They said that the banking sector shouldn’t enter into the debate given its reputation.”

Risky or not, did nobody see that the Catalan regional government and the central government have been on a collision course since 2014?

Some in the sector also point out that if they had pulled their headquarters out of Catalonia ahead of the referendum, they would have been accused of giving Puigdemont’s vision credibility. “It could have been seen as a way of pushing things forward,” said one spokesman. “It was very risky.”

Risky or not, did nobody see that the Catalan regional government and the central government have been on a collision course since 2014? Bankers and businessmen point out that the central government always reassured them that any referendum would be illegal and invalid. In recent months, the regional government put all its weight behind a referendum while Spain’s president, Mariano Rajoy, maintained it would not take place. “If what Rajoy said had turned out to be true, it could have been the end for independence,” says one CaixaBank executive. “But instead the illegal referendum took place and the police behaved in a brutal manner while the media broadcast them doing so to the world. That’s when everything went haywire. They resorted to Plan B, which barely existed. It is unchartered territory,”

Pedro Nueno, an IESE Business School lecturer with a PhD in Business Administration from Harvard, doesn’t believe many companies had a contingency plan. “In some cases, they didn’t think events would unfold as they have,” he says. “Everyone thought there would be negotiations. It’s been a bit of a stampede.”

Some businessmen admit that the potential for political and social strife was such that they chose to ignore it and trust a negotiated solution would be reached instead. But Juan Rosell, who has played a key role as a Catalan citizen and President of the employers’ association CEOE, says he tried to bring the two sides to the negotiating table without success. “Catalonia doesn’t understand Madrid and Madrid doesn’t understand Catalonia,” he concludes.

Catalonia doesn’t understand Madrid and Madrid doesn’t understand Catalonia Juan Rosell, president of the CEOE employers’ association

Another important factor is that Madrid did not take on board the pro-independent leanings of many Catalonian businessmen, particularly the small businesses and collectives that have been close to Puidgemont during the independence process. “If you want to know what the businessmen are thinking, just ask the SMEs [small and medium-sized enterprises],” said the regional president.

One Catalan businessman points out that a number of SMEs already move in an autonomous world: their customers are Catalan, their environment is Catalan and they believe that an independent Catalonia will mean a more buoyant economy, as the regional government has promised. “Don’t forget that both big and small Catalan companies have their families and friends in Catalonia. Their neighbor could be a pro-independence businessman and to take the opposite stance could be awkward,” he says.

It is generally believed that both the Madrid and Catalan governments will avoid a face off. “Because, look,” says Freixenet’s president, José Luis Bonet. “I feel Spanish and European, but I’m still Catalan and to have to take a decision like this is very painful. It’s like being torn in two. I am Catalan and I have to go. It’s clear that we and the other companies leaving are iconic in Catalonia, but you have to understand, survival comes first. The fact that people have not talked in both private and public has been a big mistake. The reason it wasn’t done was to avoid awkward situations, but problems are not solved like that. If you keep quiet, the noisy ones appear to be in the majority.”

But what consequences will these relocations have further down the road? “Until now both management and the factory was here,” says Costas. “The risk is that now we will only be left with the factory. Catalonia is a productive economy and companies won’t leave altogether but the executive side of things will be lost.” He adds, “I did think it might come to this and I said as much. But there was always someone accusing you of peddling fear.”

A rap on the knuckles for the business sector

In a Circle of Economy conference in Sitges at the end of May, Mariano Rajoy warned that Catalan independence would be “traumatic” and have “terrible economic consequences.” Spain’s prime minister also directed these words to those sitting on the fence: “Impartiality is all very well, but not always and not in every walk of life.”

There were those who didn’t appreciate this covert criticism. They said it wasn’t their job to take sides and that they had already done quite a lot as it was in asking Puigdemont to abandon his pursuit of independence and show his face in Congress. Others, however, took Rajoy’s message on board. “I understand some seek dialogue but, at this stage, it’s not the same to be on the side of those obeying the law as to be on the side of those putting the safety of the justice system in jeopardy,” said one.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.