The ‘red’ scientist who was pardoned by Franco

Previously unseen material documents the extraordinary life of the physician Rafael Méndez

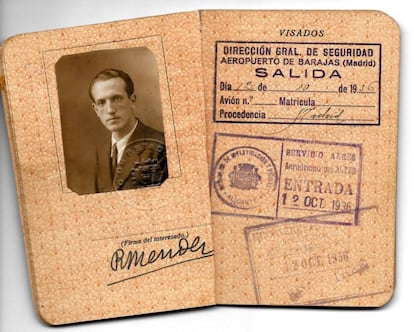

Rafael Méndez, who was born in Lorca (Murcia) in 1906, once described himself as just another member of “the youth of the era: poorly trained and disinclined to study, a reflection of the country itself in terms of our unconcern and backwardness.” Yet this youth, who had already completed his medical studies by the age of 20, would go on to play a salient role at many key stages of Spain’s convulsed 20th century.

Memorable moments include getting arrested for partying too hard with the poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, rooming with the Nobel Medicine Prize winner Severo Ochoa, traveling the world on secret missions to buy arms for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, getting hired by Harvard University, and befriending such ideologically diverse individuals as Juan Negrín, the last prime minister of the Spanish Republic, and Manuel Fraga, the information minister for Franco.

A quarter century after Rafael Méndez’s death in Mexico, where he had become a naturalized citizen, EL PAIS’ science section Materia has unearthed previously unseen material from the family archive, which is cared for by his son Juan Pablo, who also studied medicine and is now coordinator of the Obesity Research Unit at Mexico’s National Autonomous University.

Rafael Méndez was the son of a man who learned how to read and write at age 22, when he married a woman who already had those skills. The family’s small businesses provided enough income to send three sons to Madrid to complete their studies. “I did what I was told,” wrote Méndez in his memoirs, Caminos inversos (Vivencias de ciencia y guerra) (or Inverse Journeys (Experiences in science and war)). “A young man did not issue opinions […] Decisions were made for him, and he pursued whatever studies were determined by his family, friends of the family...or the village priest.”

The young student’s life changed forever during his second year at medicine school, where the new chair of physiology in 1922 was Juan Negrín, a doctor would would ultimately become the last prime minister of the Second Republic, which fell to Franco’s forces in 1939. “Our intellectual curiosity began to be aroused with Negrín,” wrote Méndez.

Negrín, who had trained in Germany, put together a team of brilliant young men that included Severo Ochoa, a future Nobel winner. But Méndez was more than a student to him. “For many years, I was his best and most devoted friend,” recalls Méndez in his memoirs.

In Madrid, Méndez roomed with Ochoa at the famous student residence Residencia de Estudiantes, where he once attended a conference by British egyptologist Howard Carter, who had recently discovered Tutankhamen’s tomb. And it was also there that he met the Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca, who later dedicated one of the poems in Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads), the one titled “Reyerta,” to his new friend.

In October 1934, at the age of 28, Méndez became the new chair of Pharmacology at Cádiz’s School of Medicine. To celebrate, his pals organized a dinner at a downtown tavern favored by bullfighters. García Lorca was part of the group, as was the surgeon Armando Muñoz Calero, who would later become vice-president of the soccer team Atlético de Madrid.

“With post-dinner gaiety, we sauntered over to Cabaret Alcázar, located in the basement of a building on Alcalá street near Sevilla street. But a small group there was bothered by all the noise we were making, and a fight broke out. The cabaret manager called in the guards, who showed up with their rifles and arrested the whole lot of us. We were hauled to the station, and from there to the courthouse at Salesas square,” writes Méndez in his memoirs. “The magistrate took statements from us; we explained the reasons for our merrymaking, and he gave us a friendly little speech, canceled the trial and let us go home to sleep it off.”

Less that two years later, the friends split up and joined opposing sides to try to kill each other in the war. The coup against the democratically elected government began on July 17, 1936. On August 18, Lorca was summarily executed by a firing squad in Granada. During the war, professor Negrín was appointed treasury minister for the Republic, and in May 1937 he took over as head of the Cabinet.

“Méndez was a trusted aide to Negrín,” says the historian Ángel Viñas, who has written about the war. Méndez, a card-holding socialist, was asked to go abroad and try to secretly purchase weapons. “In banks in Paris and the United States, there were vast amounts of francs and dollars to my name,” admitted Méndez in his biography. According to Viñas’ calculations, Méndez had around US$4.5 million (1936 dollars, that is) to his name, and a further $18 million in accounts he shared with other agents working for the Republic.

His first mission was to Algeria. He had just turned 30. “The alleged salesman was a one-eyed Arab, well dressed and good looking,” he wrote in Caminos inversos. But this man turned out to be a swindler and the mission was a failure, just like most of all his future arms-buying missions. The Non-Intervention Committee created in 1936 by France and Britain hampered arms sales to the Spanish Republic, even though Franco’s side was being aided by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

Méndez insists that he never took a penny of that fortune, and Viñas adds that “there are no reasons to doubt it.” But “the Republic’s accounts are impossible to reconstruct. There are no documents, or else I haven’t found them,” says the historian.

In August 1938, with the bloody Battle of the Ebro in full swing, Negrín called Méndez and told him to get ready to travel to Zurich with him for an international physiology conference. Méndez was dumbfounded.

“What will people say when they find out that we are going to a physiology conference in Zurich at a time like this?” he asked. “It will give them a sense of confidence,” replied the prime minister.

But there was an ulterior motive for the trip. One of the speakers on the list was Walter Cannon, an American physiologist who taught at Harvard and was a champion of the Spanish cause. Negrín wanted to talk to him. But Cannon was indisposed at the last minute and never attended the event. No foreign power came to Negrín’s aid, and on April 1, 1939 General Francisco Franco declared himself the winner of the war.

“I was in torment during the Spanish war. That is when I became fully aware, after experiencing it up close, of the ferocity of the human race. That is why I cannot agree with myself on my own political philosophy today,” said Méndez in 1982, when he received an honorary doctorate from Murcia University.

By then, it had been a long time since he was last depicted as “the plunderer of Spain’s treasure,” as the Franco dictatorship first described him.

When the war ended, Méndez fled to France, and from there to the US, where he had been offered a research position at Harvard. Four years later he received an offer from Loyola University in Chicago, and had papers published in Science magazine.

In 1946, after his wife died, Méndez accepted a position at the National Cardiology Institute in Mexico, and published research work in the prestigious periodical The Lancet.

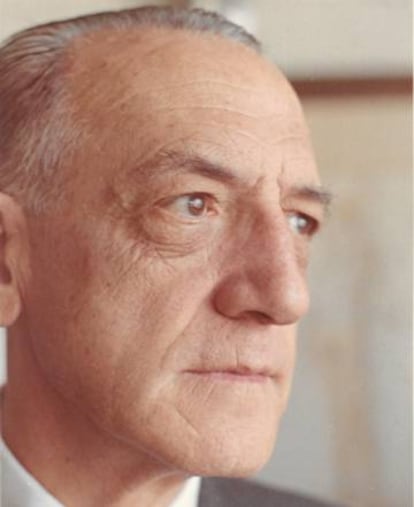

“The scientific work of Dr Rafael Méndez does not require excessive praise: it speaks for itself, and he is internationally considered one of the great researchers and masters of cardiovascular pharmacology,” said Manuel Cárdenas Loaeza, an emeritus member of the institute, at a tribute event in 2011.

Cárdenas Loaeza also noted Méndez’s enduring love of “bullfighting, flamenco and Gypsies,” and his friendship with leading figures of both fields. “How often we spent unforgettable evenings with Sabicas, Lola Flores, Manolo Caracol, la Contrahecha, Cagancho or Luis Miguel Dominguín. They all viewed him as one of their own, and used to call him Rafaelito.”

“My father was an earnest, kind, intelligent and very sociable man who had many friends,” recalls his son Juan Pablo Méndez. One of these friends was unusual, given Méndez’s leftist background: Manuel Fraga Iribarne, founder of the Spanish Popular Party (PP).

They met at a sociology conference in Mexico City in 1961, and struck up a conversation. A year later, Fraga was made information minister, and it was he who convinced Franco to let Méndez return to Spain after 25 years in exile.

“When Fraga came to Mexico, he saw the way we lived and he told Franco that my father did not keep any money from the Republic,” says Juan Pablo. The family believes that the dictator wanted the scientist back in Spain in case he should win the Nobel prize – afraid that there would be a repetition of the case of Severo Ochoa, who won while living in the US. But Méndez refused to move away from Mexico, his new home.

He acquired citizenship in 1949, and became friends with the famous filmmaker Luis Buñuel, whom he had met at the student residence back in Madrid. “The ambassador in the movie The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is named Don Rafael after my father,” reveals Juan Pablo.

Méndez also interceded in Buñuel’s name before Fraga, who lifted a ban on the filmmaker working in Spain.

“We became unconditional friends because we tell each other the truth beyond ideologies,” writes Fraga about Méndez in his Memoria breve de una vida pública (or, Brief memoir of a public life).

In 1981, a decade before his death, Méndez received the Great Cross of Civil Merit from King Juan Carlos for a life dedicated to science.

Méndez’s feelings were encapsulated in something he told his son: “I feel that my life has happened to someone else, not to me.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.