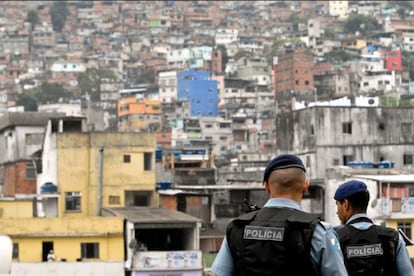

Officers charged with policing Brazil’s ‘favelas’ face uncertain future

Community police claim to have been targets of hatred and violence by residents Locals believe they will leave as soon as the 2016 Olympics in Rio are over

On several occasions each day, Gabriela passes by a vehicle belonging to the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Rio de Janeiro’s Vidigal shantytown, or favela. Two armed officers spend most of their time sitting inside, looking at their cellphones.

She greets them and they offer her some water, but most other residents prefer to ignore the officers. While some say they don’t trust the UPP agents, others believe that their stay in Vidigal is only temporary, and they will move on once the 2016 Olympic Games are over.

Most residents prefer to ignore the UPP officers because they fear reprisals from drug traffickers

“I know five people who greet the police, but usually the rest are afraid of reprisals by drug traffickers if they are seen talking to them,” says the 27-year-old woman.

Brothers Daniel, 16, and Vitor, 13, have no interest in getting to know the officers. They claim that the UPP officials have begun carrying out random personal searches – like regular police officers – on their friends in full view of local residents, making the incidents look suspicious.

But in other shantytowns such as Manguinhos, which is much more violent than Vidigal, the UPP’s presence has come under intense pressure.

“They are following an extermination policy and we are constant targets. Our children are being killed and on top of that we have to prove that they didn’t deserve to die,” says Ana Paula de Oliviera, 38, who is one of 208 mothers who have lost a child at the hands of the UPP since 2009.

Her 19-year-old son Jonatan was shot in the back during an operation in May 2014.

Rio de Janeiro state officials first organized the community force in 2008 as a pubic strategy offensive to win back control of the favelas from drug traffickers, and pacify the city’s most dangerous sectors before Rio welcomes athletes at next year’s summer Olympics, and ahead of last year’s soccer World Cup.

But while many don’t hold the UPP in high regard, the officers’ own morale has plummeted.

According to a survey taken by the Center of Security and Citizen Studies at Candido Mendes University, 60 percent of the officers polled said they felt they were disliked and even hated by the residents of the slums they patrol.

The figures show that UPP officers have a dimmer view of their roles compared to those reflected in prior surveys, taken in 2010 and 2012.

More than half of officers say they are inadequately trained while 42% complain about their safety

Little more than half believe that they are inadequately trained while 42 percent complained about their safety.

The results also demonstrate the distances that exist between the UPP and the neighbors they were assigned to protect. Only 5.3 percent said they hold regular meetings with residents, while only 14 percent acknowledged that they have tried to settle conflicts inside the neighborhood.

Of the 2,002 officers interviewed, 65.8 percent said that they have been insulted while 55.8 percent reported that objects had been thrown at them.

“Previously, the UPP had problems with its reputation, its credibility, but now we are seeing a structural problem that, if left unresolved, could pose serious risks to the program,” says Silvia Ramos, one of the coordinators of the survey.

“We have to reorganize the program. There are a series of activities, such as meetings with community leaders or strategic communications with the community through the social networks that don’t cost any money,” she explains.

Everyone believes that a community police officer is second rank to a police officer”

But Pehkx Jones, deputy secretary for Education, Prevention and Assessment, which reports to the Citizens Security unit, warned that these figures only reflect a certain period in 2014.

“The results would be different today,” he says, noting some improvements.

Nevertheless, Jones acknowledged that the program suffers from deficiencies when it comes to officer training. Perceptions about the force are also misleading, he argues.

“Everyone believes that a community police officer is second rank to a police officer – that’s true especially among young people. But that doesn’t just happen in Rio or Brazil,” Jones says.

The UPP’s future in the 38 favelas in Rio has become one of the major debates over the past weeks in Rio, fueled by the prospect that the Olympic Games are just 10 months away.

A string of violent incidents involving the UPP have helped propel the issue to the forefront. Eight UPP officers – double that of 2014 – have been killed in the line of duty so far this year. At the same time, the number of killings and abuses committed by these community officers during drug shootouts continues to grow.

English version by Martin Delfín.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.