Inside Podemos’s Madrid laboratory

The new Spanish party was created in the Complutense University’s politics faculty

Students at the political sciences faculty at Madrid’s Complutense University campus in Somosaguas have booed Rosa Díez, the leader of the centrist UPyD party, as well as the Popular Party’s Josep Piqué. At the same time, they’ve given standing ovations to Hugo Chávez, the former president of Venezuela, and Alejandro Cao de Benos, Special Delegate of North Korea’s Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries.

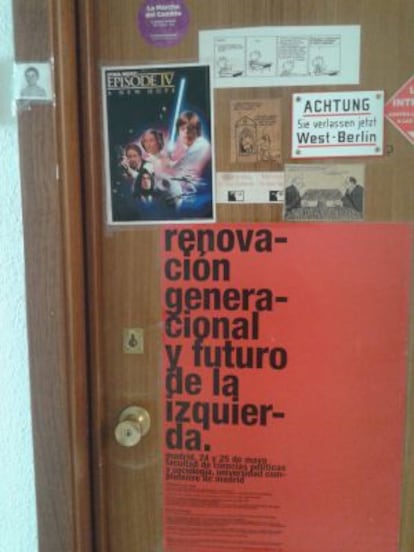

Located in the upscale suburb of Pozuelo, in the northwest of the capital, Somosaguas is where the roots are to be found of Podemos, the party that has emerged over the last year as a potential major force in Spanish politics. The brick walls of the faculty are painted with graffiti challenging the established political order created four decades ago after the death of dictator Francisco Franco – the traditional two-party system that Podemos’s supporters see as in cahoots with big business and that they dub the casta, or caste. “Against all authority,” reads one. “40 years of dictatorship, plus 35 for the tip,” says another. Stickers with the Twitter hashtag “#Castaeverywhere” litter walls, desks and chairs.

Visiting Erasmus students are often shocked by what seems like a time warp back to the 1960s and 1970s

It was in this faculty where Podemos’s founders: Pablo Iglesias, Juan Carlos Monedero, Carolina Bescansa and Iñigo Errejón created the theories they hope to have a chance of putting into practice after the municipal and regional elections in May.

But the horse trading that has followed last month’s regional elections in Andalusia, where Podemos won 15 seats out of 109, and the Socialist Party 47, has provoked a standoff between Teresa Rodríguez, the party’s leader in the southern region, who is demanding greater freedom in negotiations over a coalition government, and secretary general Iglesias, whose strategy is based on absolute control by the central committee when it comes to strategic decisions. There has already been friction between the leadership in Madrid and Pablo Echenique, Podemos’s candidate in Aragón, and it is unlikely this will be the last example. After the May elections, Iglesias and the Madrid-based leadership will no longer be the sole voice in the party. This will test the foundations created by Iglesias in Somosaguas.

There, Iglesias, Monedero, and Bescansa used student organizations and their classes to hone their arguments against what they call “the ’78 regime,” as well as perfecting techniques to put the social networks to use in spreading the word. This allowed them, over the course of just a few months, to create a party out of a popular groundswell of protest that won five seats in the European elections last year, and 15 seats in the Andalusian regional parliament. Using the campus as a laboratory to put their political ideas to the test, the three, along with Errejón, who was a PhD student there, established the organizational structure that is now being put under stress.

“Pablo Iglesias wants a centralized structure,” says José Ignacio Torreblanca, a journalist and author of a new book on the party who himself studied politics at the Somosaguas campus. “He learned at the faculty that 40 people who are active, cohesive, and efficient, can overcome larger forces that are not as well organized.

“The main enemy of all these grass-roots type organizations are themselves, their inefficiency. Iglesias understands this very clearly. All his theoretical stuff has been done at Somosaguas,” he continues, explaining that the emergence of the 15-M protest movement in spring 2011 gave Iglesias the chance to put those ideas into practice. “The faculty at Somosaguas became the headquarters where everything was planned, where the ideas were developed. This is a faculty that has always been left-leaning, but where there have also been other options.”

This is where Podemos was born, raised, and then sent out into the political world. The faculty’s administration admits that its authority is constantly subject to negotiation with a minority of the student body. More than 15 students have been arrested over the last five years, according to the Complutense. A group of 80 or so individuals who are not students have infiltrated the campus, setting themselves up there, says the university. One group of students has been given a classroom for their personal use in return for agreeing to leave a wing they had taken over in a building that was being refurbished. Some members of the teaching staff have been subjected to noisy protests, such as Moral Santín, a member of United Left who briefly sat on the board of savings bank Bankia, and was under investigation for alleged misuse of expenses. There are constant demonstrations against the EU’s Bologna Process, which reduces the length of degree and Master’s programs to three and two years, respectively.

Luis Giménez, a journalist who has also written about Podemos, draws an analogy with the Asterix and Obelix comic books. “The faculty is the Gaulish village that is resisting the Roman occupation,” he says.

Errejón describes Somosaguas as “a barometer of a generation. It’s a seedbed of ideas, an arsenal.” He founded a student group called Contrapoder that organized the protests against Rosa Díez – which Iglesias also took part in – and Santín, and also quickly joined the 15-M street protests.

“If you want to change things you need to be daring, to dare to question the existing order,” says Errejón, who is now Podemos’s political secretary, about his involvement in the protests. “Without that part of youthful militancy and without the university it would be much harder to understand all this,” he says. “It had an impact, and its traces can still clearly be seen in Podemos.”

Only Monedero has continued to teach at Somosaguas. “Monedero, as an intellectual, has had the most influence over me,” says one of his students, who has also played an active role in student politics. “He argues on the basis of his beliefs, but the good thing here is that there are also conservative teachers who provide a contrast,” he says, describing Monedero’s classes, the reading for some of which is still largely based on Marxist scholars writing in the first part of the 20th century. “In the faculty, we have always fought for justice. This is a place where student political life has always been dominated by the left wing.”

Erasmus students coming here from the rest of the EU are often shocked by what seems like a time warp back to the 1960s and 1970s, which marked the heyday of student protest in Europe and the United States. “The faculty is plural, but students who are not on the left tend to keep their views to themselves during debates,” says Rubén Herrero de Castro, a lecturer who describes himself as “conservative.”

“The faculty has always been a place of learning, but not necessarily in the academic sense,” says Héctor Meleiro, who studied at Somosaguas and was an early participant in Podemos. “What we also learn here is the importance of occupying places in the institutions so that we can push through political change: we learned that from Iglesias.”

Podemos was born out of the utopian spirit at Somosaguas, and what began as an experiment in political science has grown to be a force that could break Spain’s two-party system. The May elections will put Podemos’s theories to the test, establishing whether the ideas of its founders about changing the world here are really able to make the transition from the classroom to reality.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.