Madrid’s hungry years

A book provides insight into the solutions women found to shortages during the Civil War Laura and Carmen Gutiérrez Rueda collected recipes from survivors of the city’s siege

The abiding memory of anybody who lived through the two-and-a-half-year siege of Madrid during the Spanish Civil War is one of hunger.

As the forces of General Francisco Franco gradually won control over the rest of the country between July 1936 and April 1939, when the conflict ended, food supplies in the capital dwindled. Standing in line was a constant feature of daily life, with the more stoical ladies refusing to abandon their spot even as the bombs fell around them, in the hope of taking home a bone for stew or a sweet potato.

The main topic of conversation in many households was: What would you eat right now if you could have anything you wanted?

Lentils, dubbed “resistance pills,” were the staple that allowed countless families to survive. Housewives came up with solutions that included making omelets with orange peel or sausage out of breadcrumbs, while breaded fried onion rings had to make do for fish. Some children never saw a banana or chocolate until after the war ended, while the main topic of conversation in many households was: “What would you eat right now if you could have anything you wanted?”

A book originally published in 2003 and titled El hambre en el Madrid de la Guerra Civil (or, Hunger in Madrid during the Civil War) provides valuable insight into the solutions that women found to the food shortages.

Laura and Carmen Gutiérrez Rueda, now in their seventies, have collected recipes from around 75 of their contemporaries who lived through the siege in the Spanish capital. The two sisters, a historian and a pharmacist respectively, say in their introduction that their mother’s weight fell from 70 to 35 kilos between 1936 and 1939.

“We heard a lot of talk growing up about the hunger years during the Civil War, and we wanted to collect those stories before they were lost for ever,” says Laura. So the pair began talking to friends and family, and started visiting visiting nursing homes.

“A lot of people didn’t want to talk about the war because they had lost loved ones, or because they'd had a contact in the government or the unions and were able to access food,” says Laura, adding: “Others from different sides in the war were still arguing with one another.”

After a lightning campaign throughout the summer of 1936, Franco’s forces were brought to a halt outside the northwestern edge of the city, gradually closing the circle until March 1939, when the capital surrendered. Madrid, which already had a population of around one million people, was also filled with refugees from other war zones.

The city was protected by trenches manned by Republican forces and volunteer militias. But getting food supplies into the capital became increasingly difficult. A black market soon began to flourish, and shortages were made worse by rivalries between different factions within the Republican administration, which was obliged to issue ration cards.

As money began to run out, many families were obliged to barter belongings, say the sisters. “People would go to the Torrijos market and exchange objects for food, supplies of which the unions tended to control: a sweater for a slice of bread. One of our aunts worked for a Swiss insurance company and was paid in cigarettes, which she would exchange for food,” says Laura, adding that the city tried to retain some semblance of normality despite the privations: “People went to work, and despite the hunger and the fear, the cinemas were open, which I have to say still surprises me.”

What did people eat during the siege of Madrid? Not much: mainly lentils, sweet potatoes, gruels, the occasional piece of salted cod, an egg every now and then, but virtually no meat. Rice and fruit stopped arriving in early 1937 after Franco’s forces cut off the route to Valencia, where the Republican government had fled to, leaving the capital under the command of a defense committee led by General José Miaja.

A lot of people didn’t want to talk about the war because they had lost loved ones, or because they'd had a contact in the government or the unions and were able to access food” Laura Gutiérrez Rueda

“Cats soon disappeared, because they tasted similar to rabbits, and people just ate them. Near our house a donkey that belonged to a coal delivery company died, and it was cut up and sold for meat. Dogs were also passed off as lamb,” says Carmen.

And as the siege wore on, the impact of this poor diet began to show itself through illness and diseases such as avitaminosis, pellagra, hunger edema, and even brain damage, particularly in the case of children. “Tuberculosis continued to cause many deaths until well into the 1940s,” says Carmen. "And because of the different illnesses and problems that hunger caused, there are no figures on how many people actually died from poor diet.”

Not even death was an escape from the shortages: “There was no wood to make coffins for the dead, because it had all been used for fuel. Many of the deceased were simply buried in sacks. People wanted to cut down the trees in the Retiro park, but City Hall forbade it,” says Laura. Instead, children would swarm over the ruins of buildings that had just been bombed in search of beams and any other wood they could find.

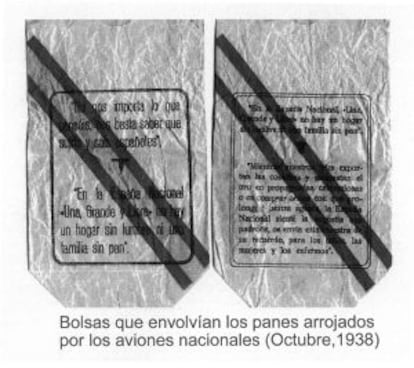

In the final stages of the siege, Franco’s forces began dropping small loaves of bread on the city. They were wrapped in a Spanish flag bearing the legend: “In national Spain, united, great, and free, there is no home without a hearth or a family without bread.” The defense committee warned residents not to eat it because the bread could have been poisoned, but most people took no notice. “There were even bootlickers who handed them in to the authorities: I saw militia members throwing them down the drains.”

Gloria Fuertes, a novelist and poet who lived through the siege and died in 1998, wrote of the suffering caused by lack of food: “Hunger, hunger. Madrid began to suffer from hunger a month after the war began. One time we went three days on a fried egg, spreading it and hiding it away… I wasn’t afraid of dying, I just had the horrible stomach ache caused by hunger.”

More than seven decades after the war ended, the Gutiérrez Rueda sisters say they are dismayed to see hunger return to the streets of Madrid, and to hear charities such as Cáritas warn of an increase in child malnutrition. “The hunger’s not the same as during those times, and nowadays you can always go to a food bank,” says Laura. “But it’s horrible that people have to search through garbage dumpers, or that the police are chasing away people scavenging for the food that supermarkets have thrown out.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.