PP’s irregular donations were not subject to tax, Agency tells judge

Report compares party financing to that of an NGO such as the Red Cross

The judge investigating alleged illegal financing of the ruling Popular Party (PP) has twice had to request a report from the Tax Agency, estimating how much tax the organization should have paid on shady donations from 2008. The Agency has finally produced its report, putting the figure at €220,167.

But the tax experts were at pains to underscore that political party donations, whether illegal or not, are not subject to corporate tax, as the examining magistrate claims.

The Tax Agency’s analysis essentially lets the PP off the hook, despite High Court judge Pablo Ruz’s view that the ruling party should have paid tax on the €1,050,000 it accepted in 2008 from donors who either went over the legal personal limit or who were barred from donating because they had been awarded government contracts.

The law establishes that any amount over €120,000 in withheld taxes constitutes a crime. The Tax Agency’s estimate of €220,167 is well above that.

But the report stresses that non-profit organizations “such as a political party, [the Catholic charity] Cáritas or the Red Cross” are not subject to corporate tax because the money reverts to society.

The authors point out a nuance: private donations would be taxable only if they were used for something other than the non-profit’s stated goals, which generally deal with social service.

According to the Tax Agency, it has been “accredited” that the PP used the donations for the goals described in its charter, such as funding campaign events, refurbishing party buildings and so on.

The report goes on to illustrate its point with the following example: if a businessman donates €400,000 in undeclared cash to Cáritas and the charity feeds 1,000 children with it – that is to say, it uses the money for the non-profit’s stated purpose – then there is no tax crime, as the donation does not constitute taxable income.

In any case, states the Tax Agency, this example would represent an administrative violation that falls under the jurisdiction of the Audit Court – the state watchdog for political parties – and has recently been subjected to tougher sanctions under the new party financing reform.

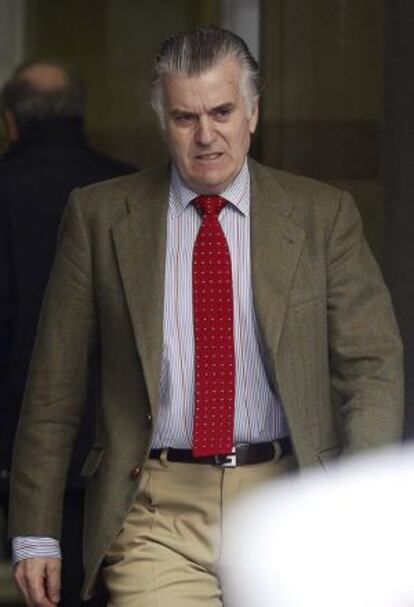

The investigation phase of the Bárcenas case – so named after the former PP treasurer Luis Bárcenas, who allegedly kept secret party ledgers reflecting illegal cash flows – has established that for nearly 20 years the PP accepted donations above the legal limit of €60,000, occasionally from donors who were simultaneously government contractors.

Examining magistrate Pablo Ruz, the anti-corruption attorney and the three judges who sit on the Fourth Section of the High Court all feel that these unlawful donations should be viewed as extraordinary income and thus are taxable.

But tax experts say that the Political Party Financing Law does not specify that non-legal donations are liable to taxation.

Even if the donations were finally found by a court to be illegal, they were used for legitimate purposes, such as refurbishing party headquarters or paying bonuses to party officials, and thus fall within the bounds of the tax exemption, says the report.

Judge Ruz was forced to issue a second, mandatory request for this report after an initial query met with a flat refusal by the Tax Agency's anti-fraud unit.

The Bárcenas scandal broke when EL PAÍS published part of his secret ledgers on January 31, 2009. The treasurer at first denied having kept them, then later admitted to it.

Luis Bárcenas is also facing a variety of other charges in connection with the Gürtel case, which is now going to trial after a five-year investigation. The PP illegal funding scandal is an offshoot of Gürtel.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.