Argentina: days away from a default

The Fernández administration must reach an agreement with the “vulture funds” by Wednesday

Argentina finds itself between the devil and the deep blue sea. The country has until Wednesday to escape and thus avoid defaulting on its debt for the second time in 12 years. The devil has many names, but they all refer to one group: the holdout creditors who are demanding full payment on Argentina’s 2002 sovereign debt and refuse to accept a 65.6% cut. President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner calls them “vulture funds.” The deep blue sea also has a few names but perhaps the most precise one is Rights Upon Future Offers (RUFO), the clause that the investors who accepted the discounted exchange bonds signed with Argentina. In short, Argentina now finds itself between “the vultures” and RUFO.

The Argentinean government registered the largest default on record in 2002 when it could not meet its obligations on $82 billion (€61 billion). There was no way to pay that enormous amount unless creditors granted Argentina a considerable discount on its debt. About 92.3% of its debt holders, those whom President Fernández calls “bondholders of good faith,” accepted exchange offers at a 65.6% discount. In order to convince investors to accept these offers, Argentina told them no creditor would get a better deal. The parties signed the RUFO clause by which the Argentinean government guaranteed these creditors’ right to demand the same conditions if another investor were to receive better terms than they had before December 2014. If Argentina, therefore, makes full payment to the “vulture funds,” the investors of good will who accepted the distressed exchange offers could sue the government for full payment on their respective loans.

I want to tell all Argentineans that Argentina is not going to default”

Argentinean President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

Argentina thus finds itself facing a difficult choice between paying the litigant “vulture funds” $1.5 billion ($1.3 billion plus interest) and violating RUFO, a situation that would allow the “bondholders of good faith” to seek more than $120 billion in compensation, more than four times the current amount of reserves in Argentina’s vaults. Such is the government’s account of its predicament.

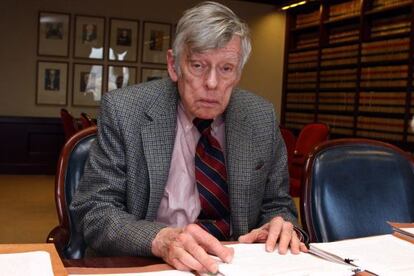

The holdouts, however, say the RUFO clause would not be applicable since the government is not making a voluntary offer to the “vultures.” Argentina must pay the suing investment funds in order to comply with a federal court order by Judge Thomas Griesa of the Southern District of New York.

Argentina’s economic advisors say payment would not likely qualify as RUFO violation but they would prefer to avoid any risk. The government, therefore, appealed to Judge Griesa for a deadline extension. If the government were to pay off the holdout investors in six months, in January 2015, there would be no risk of RUFO violation. Judge Griesa, however, has denied the request for a moratorium and has ordered the parties to sit down at the negotiation table with a court-appointed mediator, attorney Daniel Pollack.

Argentina registered the largest default on record in 2002 when it could not meet its obligations on $82 billion

Until now, their talks have been a series of non-negotiations. The funds and the government have accused and discredited one another through statements to the press in Argentina and the United States. On Thursday, President Fernández tightened the thumbscrews. “I want to tell all Argentineans, I want to tell them that Argentina is not going to default,” she said in a televised statement. “Do you know why? Because of a very simple, vital, elemental reason so obvious that I shouldn’t have to say it. Why do you think we will not default? Because those who default are those who do not pay and Argentina paid… But they will have to find some new terminology that defines the situation when a borrower pays and someone blocks the money from getting to a third party, those third parties here being the holders of the 2005 and 2010 exchange bonds who were acting in good faith.”

Fernández was referring to Argentina’s deposit of $539 million (€401 million) in the Bank of New York Mellon to pay various creditors who accepted the 2005 and 2010 exchange offers. But Griesa, that “someone who blocked” the funds, will not allow these creditors to collect before Argentina pays the three litigant investment funds their $1.5 billion. The grace period to pay “the bondholders of good faith,” and “the vultures” expires on July 30.

On Thursday, The New York Times’s business blog criticized Judge Griesa in a post that later appeared in print in the Friday edition of the newspaper. Chief financial correspondent Floyd Norris said Judge Griesa “had not completely understood the bond transactions that he had been ruling on for years.”

Translation: Dyane Jean François

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.