A vain villain, companies on the make and students who did not exist

Madrid employee training fraud probe uncovers some 15 million euros in diverted state funds

An alleged fraud case involving public subsidies for employee training in Madrid has ballooned into an affair involving millions of euros, dwarfing other similar cases that have made the news in recent months.

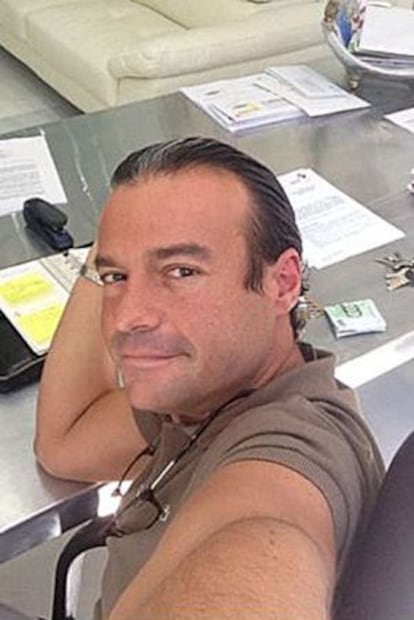

Investigators have found that around 15 million euros in state and regional funds were used to sponsor phony training programs for non-existent students. The systematic fraud went on for years, and was spearheaded by an entrepreneur named José Luis Aneri, who acted as the mediator between government agencies and the companies signing up their workers for the courses.

By comparison, a similar case involving the UGT union in Andalusia represents half as much misappropriated money, while an entrepreneur named Fidel Pallerols was recently convicted of diverting 595,000 euros using such a fraudulent system.

And they are not the only ones. The constant drip of scandals in the last 20 years evidences that, despite successive government reforms, public subsidies for employee training continue to be used as a source of informal financing by business groups and other organizations.

Training program subsidies, or manna from heaven

Politicians, unionists, businesspeople, work inspectors, training schools... over the last 20 years, all of them have, at some time or another, been involved in high-profile fraud cases involving subsidies for employee training programs or courses for the unemployed.

Investigators note it is always the same old story: courses that never took place or were not properly justified, diplomas that were handed out to people who never took the classes and forged attendance sheets. In one case involving the Madrid Training Institute (Imefe), business networks with links to the Popular Party (PP), which rules the capital and the region, fraudulently secured 8.41 million euros in employee training subsidies since 1996.

In one highly-publicized case involving a training foundation called Forcem, it emerged that thousands of courses sponsored by the EU never took place. The case led then-Prime Minister José María Aznar to change the law in an effort to reduce fraud. But investigators are currently working on 19 cases involving the Andalusia branch of the UGT union, representing around seven million euros in public money.

Meanwhile, the Andorran entrepreneur Fidel Pallerols was recently found guilty of accepting EU funds for training unemployed Spaniards, then channeling money to Unió Democrática de Catalunya, one half of the nationalist coalition currently in power in Catalonia.

Now, with the Aneri case in full swing, the government is once again announcing legislative changes to address such systematic fraud.

José Luis Aneri, a businessman from Córdoba, arrived in Madrid in 2007 and soon took over management of public subsidies for several business associations. Aneri was the contact who filed for the aid in their name, and he was also in charge of implementing the training programs through a network of companies headed by Sinergia Empresarial.

He specialized in distance courses which he allegedly provided through a digital platform. But there were no courses, and the students were not real, either. It was Sinergia workers who designed the phony coursework by copying appropriate-sounding content off the internet or from books. As for the students and their ID numbers, Aneri got lists from a variety of sources — including an association of street vendors — and used the same names again and again in as many training programs as he could. The more students he could come up with, the more money would pour in.

This method worked for a few years, until Aneri's personal life spiraled out of control. He got involved in drugs and prostitution and began spending money lavishly; those who know him say the downfall really began with his divorce in early 2013. Aneri began getting careless about his work. By the summer, his office desk was piled high with notices from the Madrid regional government, warning him that there was a lot of money whose use had not been properly justified. But Aneri showed no signs of life.

Regional technicians then began investigating the business associations that had allegedly benefited from the training programs. Around 30 of them said they had no idea Aneri was no longer justifying the subsidies. Now, the regional government is demanding that these business groups return 4.4 million euros from subsidies awarded in 2010 and 2011.

Yet the Popular Party (PP) Madrid government has been deliberately opaque about this case. It never reported the facts to either the police or the attorney's office. And the only regional official who did testify before the police on February 11 — the deputy director of continuing education — was summarily dismissed by his superiors three days later.

Besides the alleged fraud at the regional level, Aneri also extracted 11 million euros from the Spanish Labor Ministry in representation of other business groups. The largest of these is Ucotrans, the federation of transportation cooperatives, with over 350 members representing 25,000 transportation professionals, according to the corporate website.

Aneri used the same technique to secure state subsidies for these associations. In some cases, he used a list of names of street vendors and pretended to sign them up for Excel and Word computer courses, or for workplace safety training programs.

But this system required cooperation from third parties. Business sources admit that Aneri bribed the managers of some business associations with as much as 20-percent commissions if they agreed to go along with his scheme. Workers say that Aneri's standard practices with some of these execs involved big wads of money, expensive gifts and dates with luxury call girls.

But some associations feel cheated, and they have taken their case to court. A few other relevant businesspeople have been tainted by the scandal, including Alfonso Tezanos, an executive at the Madrid employers' association CEIM and president of the Chamber of Commerce Training Committee. It was Tezanos who introduced Aneri into the Madrid business world, and it was one of Tezanos's organizations, the entrepreneur federation Fedecam, that gave Aneri his first job in the field of employee training programs. Tezanos's companies are also suspected of using lists of phony students to get higher subsidies. This newspaper talked to some of the alleged students, who confirmed they never took the courses. Tezanos denies this vehemently.

While the official investigation determines whether the training subsidies were just an undercover way of funding business groups, Aneri is apparently basking in the media attention. His Facebook page includes links to newspaper articles about himself. He is already calling it "The Aneri Case."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.