Lorca’s last love letter

Newly unearthed note sheds light on why the writer failed to flee the Civil War

Seemingly indifferent to the terrible events unfolding around him and the dangers they posed, in July of 1936 Federico García Lorca was concerned only with persuading his 19-year-old lover, Juan Ramírez de Lucas, to convince his parents to allow him to leave Spain for Mexico with him.

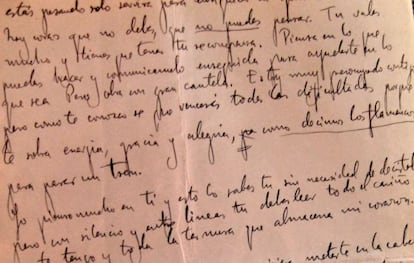

Indeed, in his letter dated July 18, the day that General Francisco Franco’s military uprising was announced, García Lorca still seems unaware of the cataclysm about to be unleashed: “In your letter there are things that you shouldn’t, that you can’t, think. You are worth so much, and you will be rewarded.

“Think about what you can do, and let me know straight away so that I can help you in whatever way, but be very careful. I am very worried, but knowing you, I am also sure that you will overcome every obstacle because you are overflowing with enough energy, grace, and happiness, as we flamencos say, to stop a train.”

Ramírez had met 38-year-old Lorca, author of Blood Wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba, in Madrid the year before, where he was completing his studies to become a civil servant. An aspiring actor, he had performed in several productions staged by Lorca, and the pair had fallen deeply in love.

Lorca was well connected and politically active, and was aware of the rumors of a military revolt against the Second Republic. He had already decided to accept an invitation to visit Mexico, but now he wanted to go with Ramírez.

The problem was that Ramírez came from a traditional provincial family of 10 children, and his father felt betrayed that his son had secretly pursued his dream of a career in acting, although he had passed his exams.

Lorca could probably have arranged for false papers for Ramírez, who was still not old enough to travel, but refused, telling his lover that he must explain things fully to his father, and get his permission to leave the country.

“I think of you all the time, and you know this without me having to say it, but silently, and between the lines, you should be able to read the love I feel for you, and the tenderness in my heart… Count on me always. I am your best friend and I ask you to be political and not allow yourself to be washed along by the river [of fate],” Lorca wrote.

According to Ramírez’s diaries, he and Lorca discussed leaving Spain together and both went to their separate homes to bid farewell to their families in the weeks leading up to the outbreak of civil war.

Ramírez details his father’s angry opposition, refusing to issue his son with papers so he could leave Spain. Lorca’s decision to return to Granada would cost him his life, and historians have often wondered why he put himself in danger.

Ramírez did not receive Lorca’s missive until July 22, shortly before all communication links broke down between areas controlled by Franco’s forces and those of the Republican army.

By this time, the poet and playwright had left Madrid, and was staying at his family’s summer home near Granada. A month later, on August 18, Lorca was seized by pro-Franco thugs and shot the next day. His body has never been found.

The murder happened during a period when Franco’s supporters took advantage of the chaos of the war to unleash a reign of terror against anybody suspected of Republican sympathies. There has also been speculation that Lorca’s homosexuality, which was well known, was also a motive.

The letter is part of a collection of papers that include a poem written in Lorca’s hand on the inside cover of a textbook to which EL PAÍS has been given exclusive access. The papers have come to light two years after the death of Ramírez, who had kept his relationship with Lorca a secret until his death, aged 91, in 2010.

The short poem, dated May 1935, is entitled Romance, and describes Ramírez as “that young man from La Mancha,” repeating: “he came, mother, and looked at me. I cannot look at him!”

It was apparently written on a journey the two lovers made to the southern city of Córdoba. The poem is handwritten on the back of a receipt for the Orad Academy in Madrid, where Ramírez de Lucas was studying.

A handwriting expert has reviewed the poem and declared that it was written by García Lorca. The poem was composed at the same time as Lorca was writing his famous “dark love” sonnets.

Lorca experts have welcomed the decision by Ramírez de Lucas to allow his personal documents to see the light, given their historical importance. Laura García Lorca, the poet’s niece, already knew about the existence of the letter, and said it could be “of enormous interest” for the archives of the Lorca Foundation, which she heads alongside her sister.

The publication of the letter and love poem to Ramírez comes in the run-up to a major exhibition that Laura García Lorca is organizing in New York.

Lorca biographer Ian Gibson, who lives in Spain, says he believes the documents will shed new light on Lorca’s last days.

Gibson says that during his exhaustive research into Lorca, Ramírez’s name came up as someone who was close to the poet in his final weeks, but that he had always refused to be interviewed.

“I did everything possible to interview him,” reveals Gibson. “I knew that his relationship with Lorca was very important. I did manage to talk to him, but he said he didn’t want to talk to me; he said that he was working on publishing something himself, and I thought he just wanted to get rid of me.”

“We can only hope that the papers will be made available soon,” says Gibson, who believes the letter is likely to be the last one that Lorca wrote. “According to my information, the painter Pepe Caballero wrote a letter to Lorca around this time, but it was returned to him unopened.”

A novel by Manuel Francisco Reina, Los amores oscuros (The dark loves), which is due out on May 22, retraces that relationship, while Ramírez de Lucas’ family is reportedly talking to a major publisher about a book deal.

Like many others looking for a way to erase the sins of the past after the Civil War, Ramírez de Lucas joined the Blue Division, the military unit that Franco sent to help Hitler after the invasion of Russia in 1941. He was wounded and decorated.

After the war, with the help of poet Luis Rosales, he found work as an architecture and art critic for the newspaper Abc, working there for the rest of his life until his retirement in the 1980s.

Ramírez de Lucas never talked about his relationship with Lorca, although it was well known among his colleagues. Not even his new partner, with whom he spent 30 years, knew about his affair with the famous writer.

In later life, after the death of Franco, he began to write about the tragic events that had marked his early life.

Shortly before his death, he handed over the documents, along with the material related to Lorca, to one of his sisters, saying he wanted them to be published.

“We knew there was a great love who in a way provided inspiration for the Sonetos del amor oscuro [Sonnets of dark love], but we didn’t know his name,” says the poet Félix Grande.

“In many conversations I had with Rosales he told me that all the days that Lorca spent hiding in his house, he kept correcting those verses nonstop. I never managed to get him to say the name. Rosales had promised Federico that he would keep the secret, and he was a man of his word,” he says.

The Peñón clue

The writer Agustín Peñón first began investigating the circumstances of Lorca’s murder in 1955, traveling from New York to Spain to talk to friends and colleagues of the poet and playwright in Granada and Madrid, documenting his conversations in minute detail.

One clue came in the form of something that Pura Ucelay, a theater director in Madrid who worked with García Lorca, remembered him saying to her: “Hey, Pura, where do you find such handsome men?”

Lorca was referring to Juan Ramírez de Lucas. “He was from Albacete, and came from a good family. Federico was mad about him. He said he would make him a great actor, that he would take him abroad, that he would perform in all the great theaters, and that he would be an internationally acclaimed actor.

“As soon as she told me about him, I asked Pura if there was any chance of meeting him, that it would be of enormous help in my work if I could find out about the last feelings of Federico. She made no promises, but said she would try. Perhaps she was trying to protect a young man who was not openly homosexual… That was when I began to suspect that perhaps the reason Lorca had not left for Mexico was because of a new love in his life.”

Peñón returned to New York with his material in a suitcase, which is where it stayed for decades. Peñón refused to publish anything, saying it would put the lives of many people at risk.

Years later, Lorca biographer Ian Gibson would track Peñón down and, after reading his notes, himself try to talk to Ramírez de Lucas, but without success.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.