The secret love of García Lorca

Juan Ramírez de Lucas never spoke about his relationship with the famed poet

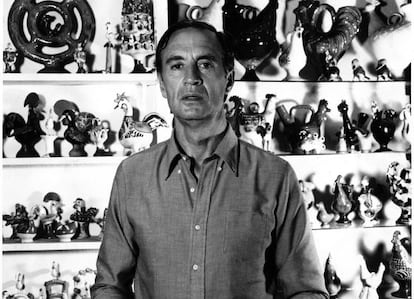

Juan Ramírez de Lucas, a journalist and art critic from Albacete who died in 2010, did not want to take his secret to the grave.

For more than 70 years he kept all the memories of his sentimental tragedy - the drawings, the letters, a poem and a diary - locked up inside a wooden box. But before dying, he handed his legacy to one of his sisters, so that she might make it public. Despite the strict silence he observed during his entire lifetime, and the support of friends who knew about the relationship but never said a word, Ramírez de Lucas did not want the memory of his great youthful affair to be lost forever. The name of his love? The poet Federico García Lorca.

They met in Madrid during the tumultuous period of the Republic, and had kept their families in the dark about their romance, given that one came from a very conservative background and the other from a family of Socialists, who were very straitlaced when it came to homosexuality.

Ramírez de Lucas was a very attractive and cultured young man, who dreamed of being an actor, and Lorca promised to take him to all the stages of the world. They were madly in love, and decided to move to Mexico. By then, Lorca was a successful author and a household name halfway across the globe; he was also tremendously reviled by violent right-wing groups in Spain. But even though his friends kept insisting that he was in great danger, the poet did not want to travel alone. In July 1936, the couple said goodbye to each other at Atocha train station. Ramírez de Lucas, who was only 19, was on his way to Albacete to seek his family's permission to go to the Americas with the poet. Lorca boarded a train to Granada to say goodbye to his own parents before leaving for Mexico.

The pair met in Madrid during the tumultous period of the Republic

Lorca experts have welcomed the decision by Ramírez de Lucas to allow his personal documents to see the light, given their historical importance. Laura García Lorca, the poet's niece, already knew about the existence of the letter, and said that it could be "of enormous interest" for the archives of the Lorca Foundation.

A novel by Manuel Francisco Reina, Los amores oscuros (or, The dark loves), due out on May 22, retraces that relationship, while the heirs of Ramírez de Lucas are in talks with a publisher over the possibility of making his diary and other documents public.

At this point in time it is unnecessary to explain that the couple's plans could not have turned out any worse than they did. Just as Ramírez de Lucas suspected, his father was enraged, and threatened to go to the Civil Guard if he attempted to leave Albacete without his permission (which was necessary at the time until the age of 21). Juan had been sent to Madrid to study public administration, and despite his good grades, the father felt that his son had betrayed his trust. His parallel life as an actor at the Anfistora Theater Club, created by Pura Ucelay to showcase Lorca's work, did not fit into his father's plans for him - much less a relationship with a homosexual poet. Otoniel, the eldest of his 10 siblings and the only one who knew about Juan's double life, tried to intercede on his behalf, but it was in vain.

Meanwhile, down in Granada, Lorca telephoned Ramírez de Lucas and encouraged him to be patient, assuring him that his parents would end up accepting it. Juan received a letter dated July 18. But that was the last he ever heard from him. Lorca's arrest at the home of the Rosales family, and his subsequent execution, remained initially obscured by the confusion surrounding the outbreak of war. But when he did find out, Ramírez de Lucas was in shock. And his feelings of guilt only grew stronger with time.

One scholar is sure that Ramírez is the real subject of 'Sonetos del amor oscuro'

After serving with the Blue Division (a Spanish unit of volunteers in the German army during WWII) to wipe his slate clean, Ramírez de Lucas returned to Madrid and rebuilt his life. But Agustín Penón, the writer who traveled to Granada in 1955 to investigate Lorca's death, found out about the relationship and made note of it in his annotations, which were later published by the historian Ian Gibson and Marta Osorio, another Lorca scholar. They were just a few lines lost in between hundreds of pages, but Lorca's lover never replied to any of the requests for interviews by either one of the researchers.

A good friend of Lorca's, the poet Luis Rosales, found him a job at the newspaper Abc, where he began a career as an art and architecture critic. He started a diary and never let go of the memories of his time with Lorca, including a poem written on the back of a receipt from Orad Academy, where he once studied. Not even his new partner, with whom he spent 30 years, knew about his affair with Lorca.

But after two years of extensive research, the scholar Manuel Francisco Reina is sure that Ramírez de Lucas is the real subject of Sonetos del amor oscuro.

"We knew there was a great love who in a way provided inspiration for the Sonetos del amor oscuro, but we didn't know his name," says Félix Grande, a poet. "In many conversations I had with Rosales he told me that all the days that Lorca spent hiding in his house, he kept correcting those verses nonstop. I never managed to get him to say the name. Rosales had promised Federico that he would keep the secret, and he was a man of his word."

That last letter from Federico to Juan, sent four days after Franco's uprising and just before mail service was interrupted, smelled of jasmine - the poet had slipped in a flower from his parents' garden between the sheets of paper. The message to Juan was that he should be strong and try to convince his parents to respect his ideas.

"You can always count on me. I am your best friend and I ask you to be skillful and not let yourself get carried away by the tide. Juan, it is necessary for you to laugh again."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.