1,000 euros a month? Dream on…

Seven years after the ‘mileurista’ was born, most young people in Spain lack a career path

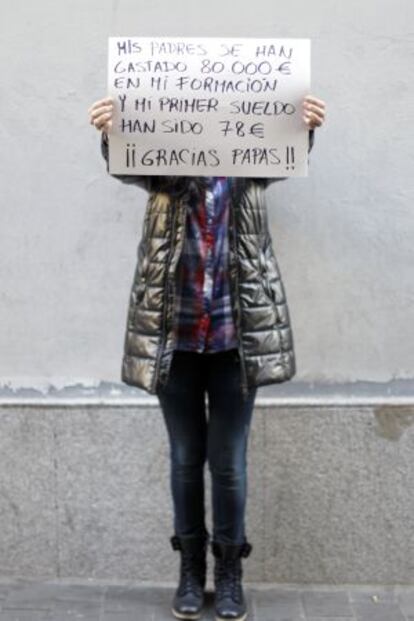

In the summer of 2005, a 27-year-old called Carolina Alguacil wrote a letter to EL PAÍS. Called I am a mileurista, it painted a portrait of a generation, and was a searing condemnation of all that was wrong in Spain’s labor market and its exploitative use of short-term contracts and low wages. Alguacil wrote: “The mileurista is somebody aged between 25 and 34, with a university degree and who speaks foreign languages, with a post-graduate qualification and training. They normally start out in the hostelry sector, and have spent long periods working unpaid as what are euphemistically called interns. After several years, you finally get a fulltime contract, but you won’t be earning more than 1,000 euros a month. But you’d better not complain. You won’t be saving any money; you can’t afford a car; and forget about children. You live from day to day.”

Rereading that letter almost seven years on, what is most depressing is that the situation for Carolina and the generation coming up behind her has worsened. “Now most of us can only dream of earning 1,000 euros,” says Alguacil. Now working as a freelance graphic designer, she says her circumstances have improved, but in her mid-thirties she still believes her career path has been truncated and that she is not earning as much as she should.

In 2005, Spain’s economy grew by 3.6 percent; the government was talking about joining the G8 group of leading economies. But even then, unemployment among the under thirties was more than 20 percent: now it stands at nearly 50 percent.

In the wake of controversial legislation introduced by the previous Socialist Party government making it easier to hire and fire, and with the Popular Party administration determined to press ahead with further reform that it admits will lead to more job losses in the short term, EL PAÍS has been talking to Carolina Alguacil’s contemporaries around Spain, as well as those about to enter the labor market. The picture that emerges is of a generation that can only dream of a time when 1,000 euros a month could be considered exploitative.

Over the course of his short working life, Madrid-based 28-year-old Pedro has offered his services for free, or been paid a trainee’s grant. Eventually, he made his first salary: 700 euros a month, working at an advertising agency. After a year it went up — to 800.

“In 2009 they started laying people off and eventually I was let go,” Pedro says. After six months on unemployment benefit, he took a job writing content for a website, at one euro a piece, earning 20 euros a month.

Most jobs receive 500 applicants. It’s a miracle if you get an interview”

He then found a job as a community manager for a website, earning 940 euros a month, but has just been laid off again. He now depends on the 90 euros a day he can earn from time to time for shifts at an advertising agency. “They pay me in cash. My approach is simple: to take any work I can.”

Pedro still lives at home, and says that his parents just don’t understand how hard it is to find work. “Most jobs receive around 500 applicants. It’s a miracle if you get an interview. There are so many people out there with experience. I didn’t think that the crisis would last this long. I can finally see now that things are not going to get better for a very long time.”

There are 10.5 million people in Spain aged between 18 and 34. And like Pedro, they are having to deal with a shrinking labor market at the same time as coping with longer-term problems such as low wages, high unemployment, an over-qualified workforce with few career prospects, high rents, and many others. The average income of this group, including the unemployed, is around 824 euros a month. Those that are working earn an average of 1,318 a month. A survey by the Polytechnic of Valencia shows that even recently qualified engineers and architects are not managing to earn 1,000 a month.

A typical case is Amanda, a 29-year-old from Valencia who earns 1,000 euros a month for a five-day week that begins at 10am and finishes at 9.30pm “with half an hour for lunch.”

She is so scared of losing her job that she refuses to even say what it is, but describes her day thus: “I leave home before the supermarket opens, and when I come home, it is closed. It’s surreal. There is no time to do anything. I am working a director’s hours and getting paid a menial worker’s wages.” But Amanda says the worst part of it is that at the same time as she feels exploited, she also feels strangely privileged. “I am terrified that I might lose my job any day.”

The figures speak for themselves: some 45 percent of unemployed under-34-year-olds have been looking for a job for more than a year. Spaniards have never been the quickest to fly the family nest, but the current situation means that growing numbers of young people that had left home are now returning to live with their parents. Others, like Beatriz Arrabal, age 32, never managed to get away. She has been without any income for the last 550 days. Despite being a qualified social worker, she has worked as a shop assistant and at a Vodafone call center, where she was paid 1,100 euros, plus around 500 euros in commission; a salary level she now sees as impossible to ever attain again.

I am working a director’s hours to be paid a menial worker’s pay”

Life is hard for those who aspire to the professions, but it’s a whole lot harder for young people who hoped that a trade would provide them with work. It did, during the construction boom, but for five young men from the same small town — two electricians, a glazier, a joiner and a metal worker — the crisis has left them with few prospects. For the under-thirties without a university degree, the unemployment rate is 55 percent.

Manuel, the glazier, is the only one of the five who has held on to his previous job; but his wages have been halved to 700 euros, and he is paid off the books. “I am not even paying my social security contribution. I’m living from hand to mouth; no future,” says the 32-year-old, who is now thinking of moving to the Basque Country, “or maybe further, like Switzerland.”

Rafa is aged 33, and until the construction bubble burst, he made a reasonable living putting metal fencing up on new apartment blocks. He is struggling to pay his 650-euro mortgage on his 850-euro wage. Domingo, age 35, fits doors. He is married and has a four-year-old son. He can no longer claim state unemployment benefit, and relies on his parents’ help. He is hoping to find work in Switzerland, where he says he can earn up to 3,500 euros a month: “But it’s tough to get in.”

Jesús and Raúl, aged 30 and 31 respectively, are electricians. Jesús was working on the Costa del Sol, and Raúl for the local council. Jesús’ unemployment benefit is about to run out. He has taken a course in looking after the disabled, and is worried about his future. Raúl says he will probably retrain as well, but doesn’t know what he will do: “I’m supposed to be getting married this year, but I can’t see it happening somehow,” he says.

At the other extreme are the overqualified. Natalia and Jesús are a couple aged 25 and 23, respectively, and are based in Granada. They represent the 37 percent of the under-thirties with university degrees or high-level skills. Natalia is a speech therapist and a lab technician. Jesús is an industrial engineer. The pair scratch a living selling insurance door to door. “Some months I earn 900 euros, and others as little as 90 euros,” says Natalia. She is optimistic about the chance to work at a privately run therapy center where she would have to bring her own clients, and pay the center a third of the 30 euros per hour she would charge. Jesús has failed to find work, and has now begun studying fine arts restoration. “I like art, and the work is quite well paid,” he says.

The government’s reforms to the labor market are aimed at making it easier for companies to hire younger people by paying them less. “The reforms are trying to do what other reforms have tried to do: to make it cheaper to employ younger people, which is simply a recognition of the failings of the Spanish labor market,” says Santo Ruesga, a professor of applied economics at Madrid’s Autónoma University. “The reforms are based on a model of generating jobs based on low costs; that is our strategy for competing in the global marketplace, and which will simply mean bad working conditions for young people. As a development strategy it is insane,” he concludes.

All my friends are leaving. Nobody seems to be taking this seriously”

Realizing that there is little hope of any improvement to the Spanish economy in the coming years, growing numbers of young people are looking for work abroad. Employment and Social Security Minister Fátima Báñez admits that the brain drain is “unprecedented.” The European Commission says that 68 percent of young Spaniards are prepared to leave to work abroad, and 32 percent say they wouldn’t necessarily come back.

There will be long-term repercussions to the brain drain, warns Almudena Moreno, an expert on youth employment. “We have few enough young people as it is after two decades of declining birth rates: this is a serious loss of human capital. More and more young people are leaving. Who will have the children we need? This is a demographic time bomb with major social and economic repercussions,” she says.

But Francisco Pérez, of the Valencia Economic Research Institute, is more optimistic: “From an individualist perspective, it is good news. It means that these young people are continuing their training. We have doctors and nurses from other countries who come here to learn. There are times when people come, and times when they go.” Juan José Dolado, a lecturer in economics at the Carlos III University in Madrid, agrees: “Emigration is good for a country in the short term. I have a niece who was earning 850 euros as a trainee architect in Spain, and is now earning 2,500 pounds in London, and she sends money home to the family. Remittances have a positive impact on the economy.”

Rafael Aníbal is a 28-year-old Madrid-based journalist who, since losing his job in November, has been thinking about moving abroad. He says that he has to run to stand still in Spain. “I have never been paid a bonus; I can’t afford to live on my own; and I can’t see things changing any time soon.”

In December he set up a blog called Pepasypepes.blogspot.com, inviting young people in the same situation as him to tell their stories. “All my friends are leaving. Nobody seems to be taking this problem seriously. If the sons and daughters of the middle classes are leaving with return tickets, then that can only mean that the working classes are leaving for good,” he says.

And while some are exercising their choice to leave, others who arrived from other countries during the boom years can no longer even afford to go anywhere except home. Elías is a 28-year-old Bolivian who came to Spain four years ago. He started out installing boilers for 700 euros a month, but has been jobless for several months now, and cannot even claim unemployment benefit. His residency permit allows him to work in Spain, but not in the rest of Europe. He now faces the tough choice of either finding a way back to Bolivia, or going to another EU country without paperwork.

“I am not going to go through the nightmare of living somewhere in the shadows,” he says. But if I had a permit, I’d be gone like a shot.” He says he would like to study IT and become a systems analyst, “but there isn’t even any work in that sector.” Before leaving, he pulls out one of the flyers he is putting in mailboxes in apartment blocks throughout Madrid, asking: “If you’re thinking of undertaking any work at home: floors, plastering or wiring. Tell us what you need. We’ll do the rest.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.